The 100 Best Movies That Were Not Nominated for Best Picture

Since the very beginning, The Oscars have had plenty of misses in the Best Picture category. These 100 are the ones we find most egregious.

With the 93rd Academy Awards upon us, we’re looking back at the most shameful misses they’ve ever had with our list of the best movies not nominated for Best Picture.

The Academy Award for Best Picture actually began its life as two awards: Outstanding Picture and Unique and Artistic Picture. But that only lasted one year. By the second Academy Awards, in April 1930, and for the decade that followed, the top prize was called the Academy Award for Outstanding Production. And while the name has changed several times over the intervening years — from Outstanding Production to Outstanding Motion Picture to Best Motion Picture to its current title, Best Picture — one thing has remained the same since the beginning: there have always been snubs. And to their shame, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences has also spent a lot of its time ignoring entire swaths of the cinematic world, from its aversion to genre cinema to its lack of respect for films with subtitles to its many years of being a mostly white, mostly male voting body that consistently overlooked the work of filmmakers of color.

Our goal for this list of the 100 Best Movies That Were Not Nominated for Best Picture is not just to highlight the films the Academy should have had on their radar. For us, this was also an opportunity to go back and look at some of the great films of all time that never stood a chance because of their genre, country of origin, or the narrow interests of the Academy. We’ve ranked them to represent the egregious nature of each instance of oversight, which as you know can be very subjective. What’s important is that no matter where each of these films is ranked, they all share one important distinction: the Academy didn’t nominate them in the Best Picture category. But they should have.

100. Oslo, August 31st (2011)

There have only been twelve non-English language films nominated for Best Picture at the Oscars, ever. That’s more than a little insane, as anyone who watches international cinema can attest. One of the many masterpieces missed by the Academy is Joachim Trier’s life-affirming but heartbreaking Oslo, August 31st. I wrote a more personal look at the film nearly a decade ago, but in short, it’s a movie that immerses viewers into two days in the life of a man who struggles to believe he deserves a life at all. It’s at times beautiful and devastating, and sweet and crushing, and it’s never less than captivating in its intimacy. The film’s greatest accomplishment, among many, is the invitation to empathy and understanding that it extends to viewers in regard to people suffering from depression. That’s no small feat, and it makes the movie a necessary masterpiece. (Rob Hunter)

99. Once Upon a Time in America (1984)

Everything Sergio Leone made beforehand was a test drive for Once Upon a Time in America. The Italian-American production is a mighty swing, and it ain’t no whiff. Leone’s gangster epic deserves to be in conversation alongside The Godfather and Goodfellas, as it cuts deep into the American Dream and the many corpses that rest below it. The film is thick and bloated but in the most satisfying of fashions. Is every scene necessary? You might not think so, but as the distributors discovered, if you start to slice a piece here and trim a strand there, the film falls apart. Once Upon a Time in America demands your time, and if you give it to the film, you’re rewarded. Watching the movie is a mindset. You have to get into it, but getting out might prove even more difficult once you do. Once Upon a Time in America is the kind of film that the second it nabs you, you’ll start spouting how it’s better than The Godfather and Goodfellas. It’s a film that demands loyalty, the unshakable variety. (Brad Gullickson)

98. Boogie Nights (1997)

How many Paul Thomas Anderson films do you think you’re about to find on this list of the most egregious Best Picture snubs ever? It’s not a spoiler to say that there will be a few, so here’s the first one. To its credit, the Academy did nominate Paul Thomas Anderson for Best Original Screenplay and both Julianne Moore and Burt Reynolds in the acting categories, making Boogie Nights the first of Anderson’s films to catch the Academy’s eye. That said, it’s also a perfect argument for the Academy’s eventual expansion of the category, for which it was more than a decade too early. Did Boogie Nights deserve to defeat James Cameron’s Titanic for the big prize? Maybe. Would it have fit nicely right alongside the other nominees (As Good as It Gets, The Full Monty, Good Will Hunting, and L.A. Confidential) in an expanded field? Absolutely. Was PTA proud of it? Yes, and that’s what matters most. (Neil Miller)

97. Silence (2016)

Martin Scorsese has had a banner decade. I mean, really a banner career, but the 2010s were really something to behold. This span saw him reach new heights with the success of the critical and box office hit Shutter Island, the eleven-time Oscar-nominated Hugo, the miraculous whirlwind that was The Wolf of Wall Street, and the monumental gangster epic The Irishman. And, in the middle of all of that, he dropped a stunning masterpiece that didn’t even make back its budget. What gives? Well, unfortunately, Silence didn’t get much box office traction or awards propulsion. It came and went, bombed at the box office, and got a single Oscar nom for cinematography that it didn’t win. It’s a crying shame, too, because — much like The Last Temptation of Christ, Scorsese’s similarly religious film that centers on the strengths and limits of devotion and faith — Silence would be a strong pick for the director’s secret masterpiece. It’s surprising that one of the most famous directors in the world is still capable of making films that are underrated, but the silver lining is that it proves Scorsese is as bold and willing to take risks as ever. (Anna Swanson)

96. Bride of Frankenstein (1935)

“We belong dead.” Three words that grip my heart every time I hear them. Bride of Frankenstein is a crushing follow-up to James Whale’s original gothic horror. The performances are more fine-tuned, the photography more sumptuous and intoxicating, and the heartache more palpable and relatable. We made Boris Karloff an icon and a cereal box character, but we cannot forget the tremendous pathos he injected into the monster. In his eyes, a thousand empathetic storytellers were born. It’s the type of performance that makes humanity better — a willing audience leaves this movie, and they enter the world a better person for having lived behind Karloff’s brow. (Brad Gullickson)

95. Black Narcissus (1947)

Black Narcissus is one of the films on this list that ought to elicit hushed, and ideally aghast, cries of “what? That wasn’t nominated!? THAT?” Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s adaptation of Rumer Godden’s novel of the same name is, without mincing words, a straight-up masterpiece. Like much of Powell and Pressburger’s work, Black Narcissus is a glorious technical marvel, Technicolor weaponized and elevated into the realm of a waking dream. The Academy had the good sense to recognize Black Narcissus’ visual accomplishments, awarding both Jack Cardiff’s cinematography and Alfred Junge’s production design. And yet, for all its obvious visual supremacy, Black Narcissus isn’t a film you can easily hold in your hands. It frequently experiments with style as substance, spills out of accepted genre boundaries, and wantonly intermingles its religious themes with shocking eroticism. I’m not saying that Black Narcissus was too horny to score a Best Picture nod. But that is also exactly what I’m saying. (Meg Shields)

94. Pariah (2011)

It wasn’t until her second feature film, Mudbound, that the Academy began to take notice of Dee Rees. But as with many of the filmmakers whose films appear on this list, they should’ve seen her talent right from the start. Her 2007 short film with the same name, from which Pariah was adapted, won awards at almost every film festival it played. And the feature-length version released four years later carried forward so many of the things that made Rees’ short special, including the beautiful cinematography of Bradford Young and a magnetic central performance from Adepero Oduye. In a year that saw the Academy nominate films like The Help and War Horse for Best Picture, it is confounding that they overlooked Pariah. (Neil Miller)

93. Touch of Evil (1958)

No one knew what they had when this film first hit screens in 1958. Even its star, Charlton Heston, acknowledged its dark noir beauty but found no heart in the story. He wanted to play the hero, and Orson Welles gave him a little two-dimensional man to wear, but you have to look to the shadows to uncover the film’s brilliance. Touch of Evil is a time bomb, like the one plopped in the car trunk at the film’s start. It ticks slowly, and it’s designed to rupture whatever mythic decency 1950s audiences foolishly clung upon. As time passed and cynicism became the norm, Touch of Evil found its audience, and each play of the film, whether in a revival house or on your iPad, stings a little sweeter and a little more knowingly. (Brad Gullickson)

92. The Devils (1971)

What kind of Academy would have nominated The Devils for best picture? A bold Academy. A brave Academy. An Academy willing and able to grapple with the putrid rot of history, imperfect idealism, and sanctimonious authority. Make no mistake, The Devils’ reputation precedes it, haunting charges of obscenity perhaps best summed up by critic Judith Crist’s condemnation of the film as a “grand fiesta for sadists and perverts.” The Devils is a harsh film with harsh subject matter. Historically, the Oscars tend to avoid anything with especially pointy edges, no matter how well-realized, performed, or acute in their criticisms. It’s true that the Academy has nominated, and even awarded, an X-rated film in the past. But the similarities between 1969’s Midnight Cowboy and Ken Russell’s political parable stop and start at their MPAA designation. The Devils is one of the most searing and upsetting visions of political corruption that’s ever been committed to celluloid. It is a genuinely dangerous piece of art. And I’m not sure the Academy really does danger. (Meg Shields)

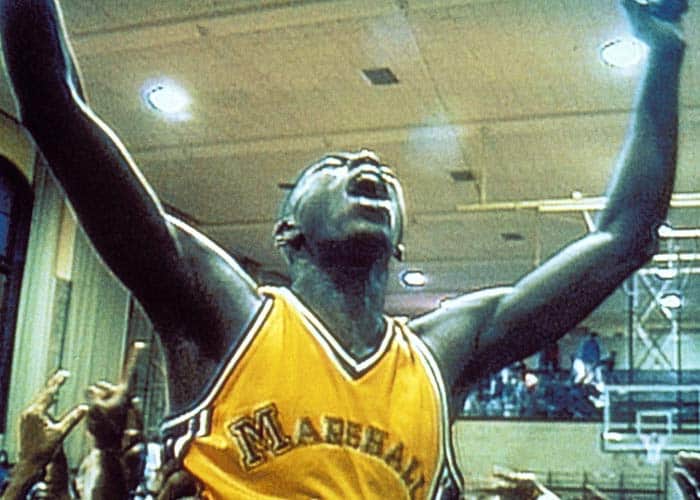

91. Hoop Dreams (1994)

It’s bad enough that Hoop Dreams was not even nominated for Best Documentary Feature. And surprising, since the film did receive an Oscar nomination in another category: Best Film Editing — which often aligns closely with Best Picture. Steve James’ 1994 film following two high school basketball players in Chicago remains one of the most famous and most popular documentaries of all time, and at nearly three hours in length, it’s the sort of epic work of nonfiction storytelling that seems like it could fit among the usual Best Picture fare. Even with 1994 being a very competitive year for the top Academy Award (this was the year of Pulp Fiction, The Shawshank Redemption, and winner Forrest Gump), Hoop Dreams’ biggest champion, Roger Ebert, named it the best film of any kind of the year, and he made a lot of great points as to why it was more entertaining and memorable than any scripted effort. It’s also definitely the most affecting, as it embeds viewers with the kids’ lives and families for years, truncated into that relatively short running time. In his best-of list, Ebert wrote, “If the members of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences don’t nominate Hoop Dreams as one of the year’s best films, they haven’t done their homework.” Sadly, very few of them did, at least in the general pool (the Editing Branch did theirs) and even the Documentary Branch failed the feature with their since-changed process. It’s recognized as one of the Oscars’ great shames. (Christopher Campbell)