The 100 Best Movies That Were Not Nominated for Best Picture

Since the very beginning, The Oscars have had plenty of misses in the Best Picture category. These 100 are the ones we find most egregious.

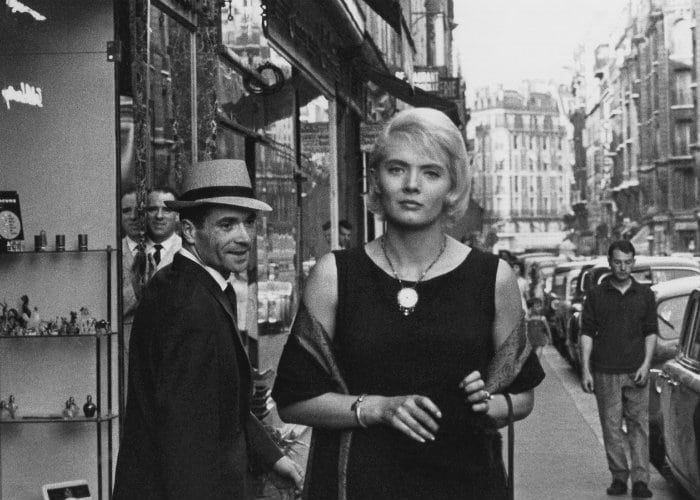

40. Cléo from 5 to 7 (1962)

Despite being a legendary French Left Bank filmmaker with more revolutionary and ingenious films than could be mentioned here, Agnès Varda only ever won a single Academy Award, an honorary Oscar in 2017. The director, whose work encompassed narrative, experimental, and documentary cinema, is most well known for her sophomore feature, Cléo from 5 to 7. Following a Parisian pop star over the course of an afternoon, the film is at once a lighthearted comedic romp and a thoughtful rumination on mortality, feminism, and identity. It’s a remarkably original and sincerely touching film and just one of many movies that Varda deserved more recognition for. (Anna Swanson)

39. Wonder Boys (2000)

I hesitate to use the word “perfect” when describing a movie, outside of Broadcast News and Street-Fighter: The Legend of Chun Li, obviously, but push come to shove I’d apply it to Wonder Boys as well. Director Curtis Hanson and writer Steve Kloves are in top form here, and the cast is spot-on from the leads on down, with the end result being a wickedly smart and surprisingly funny story. It’s arguably a coming of age tale, too, despite its central character being a man in his fifties, and his journey is one built on warmth, humor, and increasing self-determination. Wonder Boys is an endlessly entertaining pick-me-up no matter your mood, as well as a love story, a comedy, and a cautionary tale about the hazards of higher education. It is, in a word, perfect. But if more words are needed, I also wrote about it here. (Rob Hunter)

38. Mission: Impossible – Fallout (2018)

Action movies, with the exception of some historical epics, don’t tend to become Oscar frontrunners. For action films to get that rare form of recognition, being good isn’t good enough. It often seems like they have to be truly magnificent with otherworldly feats captured on screen in order to even come close to being in contention. That’s why I’m here to ask, if Tom Cruise careening through the skies in a helicopter, catapulting himself over the rooftops of London, and risking life and limb leaping from a plane doesn’t count as exceptional, what the hell does? (Anna Swanson)

37. Black Girl (1966)

Black Girl was novelist-turned-director Ousmane Sembène’s first foray into feature filmmaking, and it’s widely held to be the first feature ever released by a director from sub-Saharan Africa. That such a milestone only came in 1966, long after European and American cinema had been established, is, as with Black Girl’s events, the fault of colonialism, the French government having long imposed a law effectively banning African filmmakers from filming in its colonies. Shot six years after Sembène’s home country of Senegal became independent, Black Girl lays bare the nevertheless insidiously lingering effects of French rule on newly sovereign nations. It traverses the Atlantic to follow Diouana (Mbissine Thérèse Diop), a chic young Senegalese woman who excitedly anticipates her new job working as a nanny for a white bourgeois family on the French Riviera. Sembène employs flashbacks, claustrophobic camerawork, and twin settings (Dakar and Antibes) to juxtapose Diouna’s initial optimism with the harsh reality of her life in France, where she is fetishized, alienated, and dehumanized by the couple who employ her. Her story is not just a microcosm of the tyranny of colonialism, but also a revealing window on its stealthy persistence post-independence. Sembène extends these critiques into the film’s epilogue: its searing final moments are a radical rebuttal of the idea that apathy in the face of such injustice is any more forgivable than willing participation in cruelty. Black Girl’s achievement of such multifaceted critiques in such a short runtime (just under an hour) marks it as more than just a historical first — it’s also one of the medium’s most accomplished. (Farah Cheded)

36. Dinner at Eight (1933)

Dinner at Eight is one of the greatest examples of what made studio-era Hollywood films so magical. It’s extravagant in every sense of the word, from the elaborate sets and costumes to the unbelievable cast. MGM planned for it to be the follow-up to its Outstanding Production winner Grand Hotel from the previous year. However, the usual MGM star power didn’t win the Academy over for a second time. The film was not nominated for anything, despite several stars like Jean Harlow, Marie Dressler, and John Barrymore giving career-best performances. George Cukor directed the fun, yet sophisticated comedy that should’ve nabbed a nomination in every category. Despite no recognition from the Academy, Dinner at Eight remains a classic and a one-of-a-kind meeting of so many of our favorite classic Hollywood stars. The 1934 Outstanding Production Oscar was awarded to Cavalcade. (Emily Kubincanek)

35. Police Story (1985)

Jackie Chan will absolutely punish his body for your enjoyment. The least we can do is acknowledge his films as the best god damn action movies on the planet and give him a little gold statue for his many broken bones and ruptured organs. In a career of triumphs, Police Story is Chan’s masterpiece. The breakneck (pun intended) actioner is a nonstop adrenaline rush, and there is artistry within every frame, just not the type usually awarded by the Academy. That’s gotta change. Chamber pieces are not the only worthy tales. Double cross punch ‘em ups can speak to the human condition as much as anything My Left Foot can touch. (Brad Gullickson)

34. The Truman Show (1998)

If a film ever had its finger on the pulse of where culture was going, it’s The Truman Show. Directed by Peter Weir with a stellar script penned by Andrew Niccol, the film was released in the early days of reality television, long before Facebook or even Myspace, when “tweet” was still just a sound a bird made. This beautiful unicorn of a film manages to be a total crowd-pleaser while serving up some serious food for thought. As unknowing reality star Truman Burbank (Jim Carrey in one of his best roles to date) slowly realizes that the world around him is a lie, the film goes a step further by including the gaze of his ardent fanbase, who root for Truman to escape the cage he lives in — only to have a moment of realization at the end of the void his escape creates in their own lives. While not quite prophetic, a lot of the questions asked here about reality, artifice, and how technology and our relationship with screens impact our ability to connect with people feel more relevant than ever. It’s art, it’s entertainment, it’s asking big questions; The Truman Show feels like everything the Oscars should be celebrating, but it didn’t even score a Best Picture nomination. (Ciara Wardlow)

33. Planet of the Apes (1968)

Everyone remembers the first time they saw Planet of the Apes. “God damn you!” screams Heston, smashing his fist upon the apocalyptic shores lapping at Lady Liberty’s feet. We are our own undoing. We gotta turn it around, or the next species will rise in our place. Maybe they should. The ending burned into our brains. Yet, why could the esteemed Academy not toss them a little gold man for anything other than the technicals? The questions Planet of the Apes raises, about humanity’s insatiable desire to kill itself and the religious fallacies we construct to mask our misdeeds, roar as loudly today as they did in 1968. The film consumed conversation after its release, but simply because it is a science fiction movie, the Academy could not see the brilliance before them. These genre walls have to come tumbling down. (Brad Gullickson)

32. Videodrome (1983)

Don’t you want there to be a Best Picture nominee where a man pulls a gun out of a gynic slit in his own stomach? I absolutely do not think that Academy voters have the guts when it comes to David Cronenberg’s early, more visceral, body of work, including Videodrome. He’s a director who has smuggled some of the most prescient and striking modern theses into nightmarish visions of undulating technology and ambiguous flesh. And the Academy has proven themselves (what’s a charitable word?) unreceptive to the “low-brow” machinations of genre, gore, and anything remotely icky. No matter how acute or biting a film’s critical takedown of our problematic relationship with technology may be, the Academy has a weak stomach and a strict “no blowing up villains with cancer-guns” policy. (Meg Shields)

31. The Farewell (2019)

Where were you when you first watched The Farewell and how hard did you cry? Based on actual events in director Lulu Wang’s life, The Farewell is a story about navigating Chinese-American cultural identity in the face of family tragedy. And yet, this film by a Chinese-American director about a Chinese-American character was considered, by the Academy, a foreign language film. The Farewell was a central film, alongside Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite, in the year’s continuing debate about what makes a film considered “foreign” and the Academy’s seeming disdain for films with subtitles. Tales of the American Dream extend beyond whiteness and speaking English; they are films like The Farewell that examine what it means to be defined as an American through the lens of immigrants. (Mary Beth McAndrews)