The 100 Best Movies That Were Not Nominated for Best Picture

Since the very beginning, The Oscars have had plenty of misses in the Best Picture category. These 100 are the ones we find most egregious.

30. Ikiru (1952)

Numerous films have been shafted by the Academy over the years, but again and again, it’s non-English language movies that miss out most often. Too many people have an aversion to subtitles, and while that’s evident today, it was no different over half a century ago. Akira Kurosawa’s Ikiru is a film that deserves accolades and eyeballs, but it has to start with a patient, controlled viewing where the film’s quiet beauty and nuanced narrative won’t get lost in the noise of daily life. I’ve written elsewhere on the film’s power to heal and transform a viewer’s wavering faith in humanity, so I’ll put it more succinctly here: Ikiru is a soothing balm for your very soul, and while an Oscar nomination would have been great back in 1952, I’d be even happier if more of you gave it a first-time watch nearly seventy years later. (Rob Hunter)

29. The Night of the Hunter (1955)

Charles Laughton’s The Night of the Hunter is one of the most poetic thrillers of all time. The monochrome, yet incredibly dynamic look of the film is cinematographer Stanley Cortez’s crowning achievement, even though it was not one of the films he was nominated for by the Academy. Cortez, Laughton, and the cast of phenomenal actors like Robert Mitchum, Shelley Winters, and Lillian Gish were all ignored by the 1956 Academy Awards. Today, we consider The Night of the Hunter to be one of the best examples of film noir cinematography, but when it was released, critics and audiences received it with lukewarm appreciation at best. Mitchum’s evil evangelical character ruffled the still-influential Christian organization feathers, so its commercial failure was not a surprise. The fact that the Academy and conservative audiences did not reward The Night of the Hunter when it was released makes it even cooler today. The Best Motion Picture Award of 1956 was given to Marty. (Emily Kubincanek)

28. Daughters of the Dust (1991)

In 1991, Julie Dash became the first African-American woman director to have her film distributed nationwide in theaters. It’s a gorgeous film that explores the lives of three generations of women in a non-linear way, expansive and lush both visually and in the depth of its story. This is the kind of strikingly original film that the Academy should have been championing not just in 1991, but in every year of its existence. A singular vision from an immensely talented storyteller. Unfortunately, the Sundance Grand Jury Prize nominee was ignored completely by the Academy. And Julie Dash spent decades after having her talent ignored by Hollywood. And while recent years have seen a resurgence of people discovering and re-discovering the film, no amount of acclaim decades later can wipe away the shame of Hollywood’s failure to recognize and reward the talent of Julie Dash in the early-’90s. (Neil Miller)

27. Never Rarely Sometimes Always (2020)

In Never Rarely Sometimes Always, director Eliza Hittman wants to tell the truth about abortion, healthcare, and the terror of being a young girl. However, such a focus on the reality of accessing healthy reproductive care angered the old white male majority that makes up the Academy voting body. One such voter, filmmaker Kieth Merrill, personally wrote Hittman and said he has “zero interest in watching a woman cross state lines so someone can murder her unborn child.” These conservative politics reduce Hittman’s heartbreaking film into nothing but liberal propaganda. But it is so much more than that. This is Hittman depicting just how difficult it is to get an abortion, how expensive the process is, and how little support young women receive in trying to protect their own bodies. Even more than that, this film is an indictment of how young women are so often sexualized and preyed upon by older men, then thrown away or blamed. Being a young woman is so dangerous, yet this is a film seen by Academy voters as highly political and offensive, which in itself showcases the Academy’s disregard for the female body. Hittman’s Never Rarely Sometimes Always does not strive to push any particular agenda; all she wants to do is merely portray the harrowing truth about what it means to be a young woman. (Mary Beth McAndrews)

26. To Be or Not To Be (1942)

From today’s perspective, it’s hard to believe how Ernst Lubitch made To Be or Not To Be, a comedy making fun of Nazis, during World War II and got away with it. But he did, and it is one of the best comedies ever made. Not only is it daring, but it is downright genius. The dialogue and physical comedy are unmatched. It seemed impossible for Carole Lombard to outdo her Oscar-nominated performance in My Man Godfrey, but she does as a theater actress turned spy in this movie. Her top-tier comedy performance was even more poignant since To Be or Not To Be was released after her sudden death the year before. The only Academy Award the movie was nominated for in 1943 was for Best Music, which is one of the last things the movie is remembered for today. The Outstanding Motion Picture award was given to a more serious and dramatic World War II film, Mrs. Miniver. To Be or Not To Be may have been snubbed by the Academy, but it gets even more impressive as time passes. (Emily Kubincanek)

25. The Florida Project (2017)

Depicting the rough-edged world of Florida motel life through the rose-tinted lenses of a young girl who lives teetering on the edge of homelessness with her marginally employed mother, The Florida Project is the sort of film that could have easily nosedived straight into trauma porn in the hands of a filmmaker other than Sean Baker. Featuring stellar performances all around, gorgeous visuals, and a drama through and through, The Florida Project could have been a perfect Best Picture choice in a contentious year that split the vote so badly the Academy managed to stumble its way into giving the top prize to a sci-fi feature for the first time ever. (Ciara Wardlow)

24. Blade Runner (1982)

As is often the case with the Academy, films that breach new territory are seen as more of a threat than a welcomed change. Ridley Scott’s innovation in genre was probably off-putting to the Academy, if the fact that Blade Runner was a sci-fi film didn’t disqualify it from the get-go. Academy voters are allergic to genre fare, and even more so, they’re allergic to patience fare. Things must be fast, dramatic, and recognizable. Each year, they talk in The Hollywood Reporter’s annual anonymous Oscar voter interviews about how they believe a certain respectability politic must be upheld (which is to say, a film must look and feel and churn a certain way in accordance with Hollywood cinematic tradition) in the work of art (and even the publicity of it). But Scott, who has more than one film on this list, has proven himself a director more concerned with creativity than rule-following, even if he maintains a spot among Hollywood’s integral elite. Blade Runner’s technical wizardry, aesthetic wonder, and slow-burn pace prove it. (Luke Hicks)

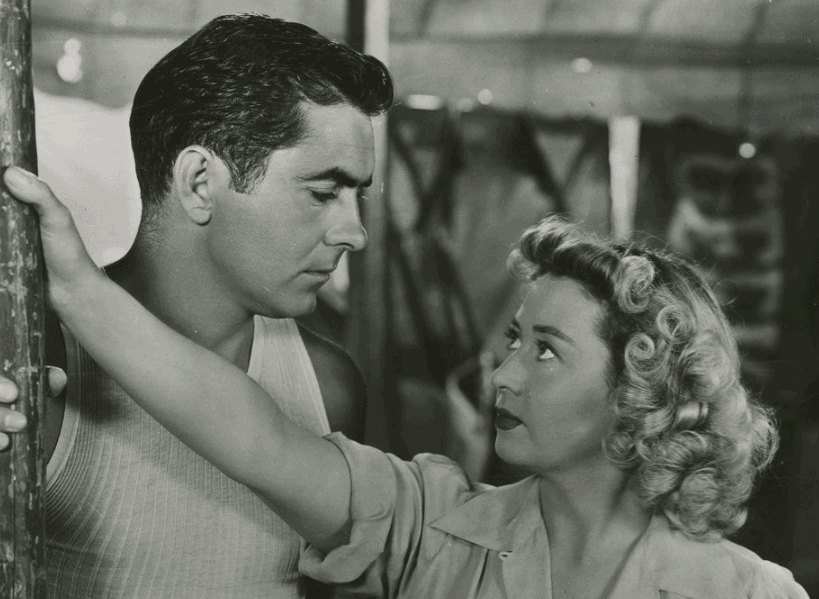

23. Nightmare Alley (1947)

Nightmare Alley doesn’t look or behave like most noirs. It’s a massive movie, with a gargantuan budget behind it and a smoldering handsome lead in Tyrone Power. The actor wanted to prove his metal on this flick and separate himself from the swashbuckling square-jaws he made his name portraying. Power’s devious Stanton in Nightmare Alley will definitely make you forget his Zorro. The character is a hungry wretch who stomps over others but feels a little bad about it after the fact. The psychological torment is where the film shines, giving Power the space to buck against audience perception. The film gets low and looks good doing it. (Brad Gullickson)

22. The Thing (1982)

Much of John Carpenter’s career can be summed up in that moment from Back to the Future where Marty McFly (having wilded out on an electric guitar) consoles his scandalized 1950s audience with the line: “I guess you guys aren’t ready for that yet, but your kids are going to love it.” The Thing is the most striking example of Carpenter’s tendency for retroactive success. Now heralded as a top-shelf benchmark of everything from practical effects to ensemble horror, The Thing did the commercial and critical equivalent of a pratfall when it premiered in 1982. The Thing is absolutely a Best Picture in the hearts and minds of genre fans the world over. But the only way it could have scored a Best Picture nomination in the early ’80s would have been if the Academy voters all drove time-traveling DeLoreans. (Meg Shields)

21. Psycho (1960)

Take a moment to imagine watching Psycho for the first time, without full access to Norman Bates’ biography or Alfred Hitchcock’s trickery. Janet Leigh steps into the shower, the water comes pouring out, and the shadow fills the doorway. The curtain rips back, the knife shines bright, and Bernard Herrman’s score carries the murderous swings south. The shock had to be tremendous, and even though I crave to experience that cinematic surprise, I don’t really miss being a part of it. Psycho is more than its twists and turns. The film is seemingly baked into our DNA, and I came into this world knowing its plot in totality. However, when I finally sat down to take it all in, the film still managed to rock me. That’s power. Knowing what’s coming and still falling victim to it. (Brad Gullickson)