The 100 Best Movies That Were Not Nominated for Best Picture

Since the very beginning, The Oscars have had plenty of misses in the Best Picture category. These 100 are the ones we find most egregious.

60. Election (1999)

Comedies aren’t typically the films you see nominated for Best Picture, and they win even less often. The reasoning rests in line with the same school of thought regarding genre fare — they’re just not “serious” enough — and while it’s been changing in recent years to some small degree, it remains unfortunate awards season truth. But 1999 was an especially egregious year as not only did American Beauty win (gross), but Alexander Payne’s Election never even nabbed a nomination. A wickedly dark comedy populated by poor saps and the effortlessly cruel, the film uses its high school setting to capture the intricately twisted details of relationships between siblings, lovers, teachers, and students. It walks a fine line straddling both the very funny and the very mean. Matthew Broderick and Reese Witherspoon headline, and both are fantastic, but the cast is pitch-perfect on down the line. Smart movies that dare to give viewers cruel, fragile, imperfect protagonists deserve more love. (Rob Hunter)

59. Meet John Doe (1941)

Frank Capra released eight movies between mid-1933 and mid-1941 (after which he’d famously commit to American propaganda efforts during World War II), and of those eight, six were nominated for Best Picture. Two of them won the award. Now, it’s not exactly a coincidence that Capra was also the Academy’s president during most of these years (overlapping with his co-founding and heading of the Directors Guild of America). He even hosted the awards ceremony the one year that he didn’t have a horse in the race. His first film following his Academy leadership, Meet John Doe, was also his first in five to be excluded from the Best Picture category. Yet its everyman-turned-hero narrative continued in some of the thematic traditions of those that were honored, particularly Lady for a Day, Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, and Mr. Smith Goes to Washington. However, with a darker, more melodramatic tone and — as Warner Bros. hyped it as — Capra’s most controversial story yet (a story that did receive a nomination). While not as fun or politically fluid as the director’s other films of that era, I think especially for the ways in which it departs from Capra’s mold it should have been given the same attention at the Oscars as the rest, as a way of appreciating a filmmaker’s evolution. (Christopher Campbell)

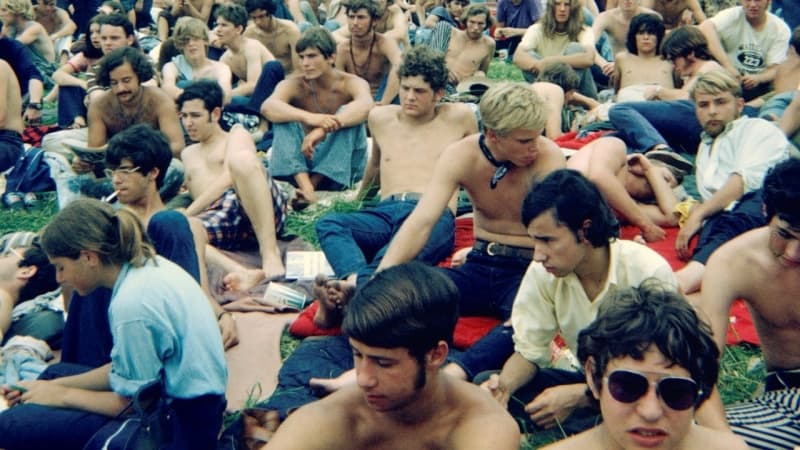

58. Woodstock (1970)

Not to spoil the rest of the list, but this is the highest placement for any documentary, and if you’ve been paying attention, you’ll know it’s only the third on this list of one-hundred. And all three are from before this century and are fairly retrospective considerations. Not to call ourselves out as a team, but that’s just how little anyone thinks about nonfiction when thinking about the Academy Award for Best Picture. Is Woodstock the greatest documentary ever? No. It’s not even the greatest concert film (though it’s close). But when we’re looking back at documentaries that could have and should have been nominated for Best Picture even by the rules of its time, Woodstock had great chances. It’s the most nominated documentary ever, having been up for not just Best Documentary Feature (which it won) but also Best Film Editing (credited to Thelma Schoonmaker, though it was a six-person team, including Martin Scorsese and the doc’s director, Michael Wadleigh) and Best Sound. Woodstock was also one of the top five highest-grossing movies of 1970, behind four movies that did make the Best Picture cut for that year. Woodstock the film is not simply a record of the iconic event — in fact, it’s a little loose with chronology — but it’s still a fantastic document of the feeling of the event as well as a cultural masterpiece in its own right. (Christopher Campbell)

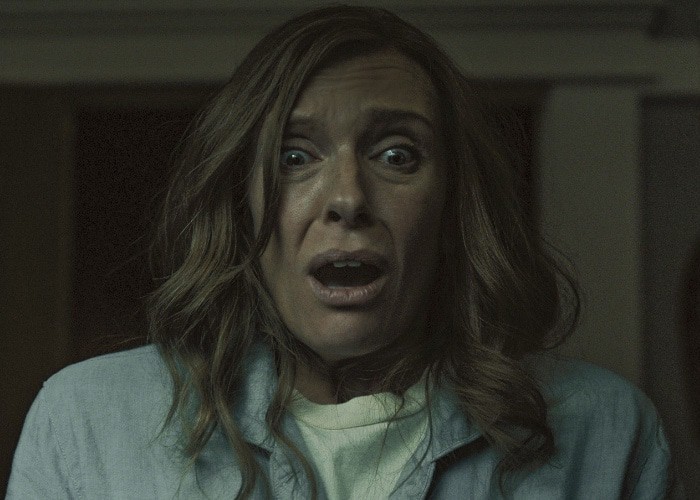

57. Hereditary (2018)

After the genre surprises of the 2018 Academy Awards — from Get Out winning Best Screenplay to The Shape of Water sweeping best director and best picture — there seemed to be hope for the horror genre as voters seemed to finally get the artistry behind these films. Unfortunately, the trend did not continue upwards, as Ari Aster’s Hereditary was snubbed across the board. Aster took the tried and true tropes of the haunted house and possession film and created something so uniquely terrifying through disturbing imagery of the destroyed human body and the nihilism of the inevitable. Toni Collette’s performance as Annie, a grieving mother, was award-worthy alone, showcasing her ability to completely pour herself into a character full of anguish, rage, and total terror. Aster’s debut was more than just a horror blockbuster; it was also a brief moment of unity across (most) moviegoers who could appreciate the fear and the beauty of Hereditary. (Mary Beth McAndrews)

56. Local Hero (1983)

Local Hero follows an American oil company representative sent to a remote Scottish fishing village to buy the town in order to build a refinery. Initially a fish out of water tale, the film becomes a beautiful and deeply rewarding take on the unlikely connections between people and places that can crack even the toughest of establishments. This lowkey and charming as all hell comedy-drama is exactly the type of film that the Oscars should take better notice of. All too often, it seems as though “most” is rewarded over “best.” The most acting — intense physical transformations and loud but hollow monologues — trumps subdued introspective performances. Here, under the direction of Bill Forsyth, the characters are brought to life with such tenderness and vibrancy that it’s impossible to not love even the most minor of players. Genuinely funny and heartfelt without ever being showy or sentimental, Local Hero is a rare gem that deserves to be widely regarded as a modern classic. (Anna Swanson)

55. They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? (1969)

Sydney Pollack’s portrayal of barbaric class division through 1930s dance marathons was always going to be too bleak for the Oscars, just like how it’s too bleak for the average unsuspecting viewer. That’s a terrible reason for a film as gut-wrenching and memorable as They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? to go unseen, but the Oscars adore popular opinion. Piling on the demerits, Jane Fonda, one of the most controversial figures at the time, led the film with tactile contempt. With her fiery approach at the center, They Shoot Horses might as well have been holding Academy voters at gunpoint. The themes at work are forward and sharp. And the bourgeoisie onlookers in the stands growing ever more feverish as the contestants struggle to hold themselves up were most certainly fashioned with the most despicable of the Hollywood elite in mind. It is, perhaps, the least surprising Oscar snub, but, in merit, a snub nonetheless. (Luke Hicks)

54. Brief Encounter (1945)

Brief Encounter may lack the imposing setting and sweeping narrative of a David Lean epic, but in sheer emotional force, this impassioned portrait of extramarital love is no less a timeless titan of cinema than Lawrence of Arabia or The Bridge on the River Kwai are. It’s an intensely psychological affair, with Celia Johnson’s confessional narration ushering us right onto the battlefield of a brutal war between propriety and desire as her housewife blindly stumbles into love with Trevor Howard’s married doctor. Impressively for its time, Brief Encounter never strikes a sordid note, with Lean empathetically framing his couple as entirely blameless victims of cruel circumstance. Stifled by social mores, their self-restraint would be torture to witness were it not for Lean’s use of vivid expressionism to invoke the shocking violence of love: trains roar and steam erupts out of chimneys, the only catharsis we’ll get while Johnson and Howard try to retain decorum in the pressure cooker of their unconsummated affair. Though it earned nominations in the Best Direction, Best Actress, and Best Adapted Screenplay categories, this exquisite rendering of the agony and ecstasy of accidental love was inexplicably left out of the Oscars’ main race. (Farah Cheded)

53. The Searchers (1956)

John Ford’s The Searchers is one of the best Westerns of all time, standing out even in Ford’s and star John Wayne’s extensive filmographies. However, this film was excluded from the 1957 Academy Awards nominations, including in the Best Motion Picture category. The Academy favored another Western from the same year, George Stevens’ Giant. But The Searchers contains the same humility and emotion as Giant while being incredibly exciting as well. It upholds what we all love about the Western genre: rugged characters turning soft, brutal confrontations, and unforgiving landscapes. The Searchers remains one of Ford’s best films and still makes my jaw drop with every passing frame. It had proved, like so many other great Hollywood films, that it didn’t need Academy recognition to make a lasting impact on cinema. Great filmmakers that followed Ford, like Martin Scorcese and Paul Schrader, name The Searchers as a major influence on their films. The Best Motion Picture award for 1957 went to Around the World in 80 Days. (Emily Kubincanek)

52. Se7en (1995)

Everyone loves a crime thriller where two cops with opposite personalities come together to fight the bad guy and restore justice to the city. But what happens when good can’t defeat evil and there’s nothing left but a deep sense of emptiness? David Fincher explores such a world in his 1995 film Se7en. In an unnamed city full of rain and gloom, a serial killer commits murders themed around the seven deadly sins. Two detectives, played by Morgan Freeman and Brad Pitt, must go on a harrowing journey to discover the worst humanity has to offer. Along the way, they grapple with faith in God, faith in the justice system, and faith in themselves. It is a film drenched in dread, where the sun never shines and the bad guys always get away. In this city with no name, Fincher is able to create both a hyper-specific tale about a serial killer and a universal message about the futility of justice. While violence is by no means frowned upon by the Academy — Fargo was nominated for best picture in 1996 after all — Fincher’s brand of violence pushes the boundaries of such imagery into new and horrifying directions. (Mary Beth McAndrews)

51. In the Mood for Love (2000)

Filmmaker Wong Kar-wai is a master of vivid color, non-linear storytelling, and telling beautiful stories about how we are all incurably lonely despite desperately longing for connection. In what is arguably his masterwork to date, two neighbors are brought together by the discovery that their spouses are having an affair with each other, only to deny their own burgeoning connection out of an unwillingness to sin as they have been sinned against. The imagery here is so powerful it burns itself into your brain, and by the end, your heart feels carved up like a pumpkin in late October, but it hurts so good. Generally speaking, the Oscars allow for about one non-English language film max to claw its way into nominations in categories beyond Best International Feature, and In The Mood for Love had the misfortune of being released the same year as Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon. File this one under “would have swept the Oscars if it was in English.” (Ciara Wardlow)