The 100 Best Movies That Were Not Nominated for Best Picture

Since the very beginning, The Oscars have had plenty of misses in the Best Picture category. These 100 are the ones we find most egregious.

80. Pride & Prejudice (2005)

Joe Wright’s exhilarating take on the Jane Austen classic revitalized a genre often considered too simpering and corseted for a place in modern cinema and transformed our expectations of what a good period drama could look like — and, more importantly, feel like. Rejecting contemporary notions of restraint, Pride & Prejudice instead unabashedly embraced physicality and feeling in a way that makes watching it still feel like a visceral, intensely subjective experience. This is one of the most alive, electric literary adaptations in recent cinematic history. Just try and find a film of this kind that has had as many gallons of digital ink spent on the thrilling immediacy of a single shot (Darcy’s erotically charged finger-flexing) as Pride & Prejudice has. Romance is just one of the film’s triumphs: its imaginative approach to adaptation produces dynamic results in every corner, from its embrace of “muddy hem” realism and wheeling long-takes to its modernizing interpretation of contemporary social relations. The Academy recognized some of Pride & Prejudice’s virtues in its acting and craft nominations but neglected to find a place for its bewitching charm in that year’s self-serious Best Picture roster. (Farah Cheded)

79. Tokyo Story (1953)

Tokyo Story is the slice of life movie. Its characters may not be duplicates of the family you know, and its setting may not be a mirror for your environment, but in drilling into specificity, Ozu reveals universality. The film meanders, and many of its great twists occur offscreen, but every action is felt catastrophically. You feel Tokyo Story in your bones. These people are the people you know and possibly take for granted. Ozu has you reevaluate your surroundings and the people who populate them. Whenever you’re feeling out of touch, or distant from the Earth beneath your feet, pop on Tokyo Story. It’ll center you quick. (Brad Gullickson)

78. Magnolia (1999)

As our list shows, the Academy seems to have a thing for undervaluing the work of Paul Thomas Anderson. And one can only imagine a world in which it was Magnolia that ran the table at the 72nd Academy Awards, not American Beauty. While not completely overlooked — the film did see nominations for Best Supporting Actor (Tom Cruise), Best Original Screenplay, and Best Song (Aimee Mann’s “Save Me”) — Magnolia is the kind of epic that should have ended up in the Best Picture race. It features an incredible ensemble cast, ambition in every aspect of its filmmaking, and a Golden Bear win at the Berlin Film Festival, for good measure. Perhaps its three-hour-plus runtime was too much for Academy members. Maybe it was too complicated. They should be ashamed either way. (Neil Miller)

77. The Fly (1986)

The Fly features one of the most affecting depictions of mortality ever put to film. All those (Academy Award-winning) prosthetics are a means of engaging with the existential reality that we all will have to watch people we care about rot, decay, and succumb to sickness. The Fly meditates on this heartbreaking fact with loose fingernails, sloughing jaws, and a visceral update on a B-movie premise that remains, to this day, a landmark showcase of practical effects. The Academy has largely been allergic to the abstractions that form the backbone of the horror genre. They balk at subversive expressions that challenge literalism and dabble firmly and brazenly in metaphor. Their loss. (Meg Shields)

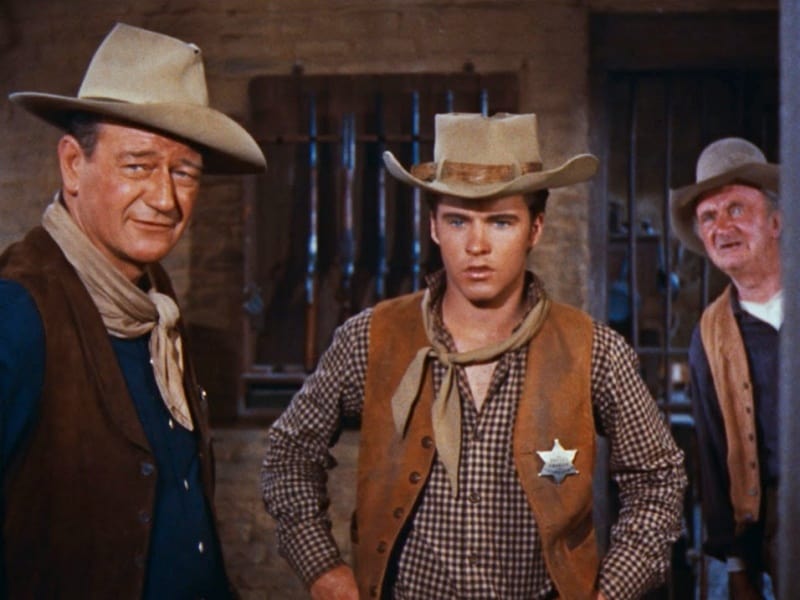

76. Rio Bravo (1959)

Howard Hawks watched High Noon and laughed. Gary Cooper running around town, begging for help? That’s no way for a cowboy to behave. A gunfighter looks to no one but themself. Rio Bravo was Hawks’ middle finger to High Noon’s Fred Zinnemann, and as such, the flick is an incredibly macho hard-on of a movie. John Wayne fortifies his bunker and prepares for trouble. He’ll accept a little help, but he won’t ask for it. His shootist is all confidence, and he carries it in his strut and his trigger finger. Rio Bravo spends its runtime ratcheting tension, waiting for evil to arrive so the Duke can smite it. It’s everything you love and loathe about the American Western. Accept it on its terms or not, Rio Bravo doesn’t care. Award its machismo or don’t, Rio Bravo doesn’t care. It does what it wants. (Brad Gullickson)

75. The Age of Innocence (1993)

Martin Scorsese can do anything. Daniel Day-Lewis can do anything. Here, they get to show off their unparalleled skills in a period piece untainted by Cameron Diaz attempting an Irish accent. Scorsese manages to translate the soul of Edith Wharton’s novel to the screen while putting his own stamp on it and captures the book’s quietly heartbreaking finale perfectly. “Just say I’m old-fashioned. That should be enough.” Just tear my heart out, why don’t you. For a filmmaker so well known for gangster epics, Scorsese really understands that sometimes ending with a bang means ending with a whimper. Not only is The Age of Innocence in the elite club of truly great movie adaptations of books you might have had to read in high school, but it also seems like exactly the sort of film the Oscars usually love — a high-society drama of ballrooms, betrayals, and soul-destroying emotional repression — and yet for some strange reason, they didn’t bite this time. For shame. (Ciara Wardlow)

74. The Third Man (1949)

The Third Man is a moody soak. As it starts, you wade into its world and attempt to gain balance alongside Joseph Cotton’s bewildered novelist. In World War II’s wake, rats swarm into Vienna, looking to claim scraps as kingdoms. Somewhere in this rubble, Harry Lime (Orson Welles) took a bite and got himself killed. Why? The answers are not as satisfying as the questions, but Cotton can’t resist the game. Carol Reed’s film defines both the aesthetics and the morality of noir, and its ability to gut-punch remains decades later. The Third Man is essential cinema, and it’s absurd that it never made its way into the Best Picture conversation, but absurdity is where this film lives. (Brad Gullickson)

73. Bringing Up Baby (1938)

Perhaps Howard Hawks’ Bringing Up Baby was too zany for Academy members, but it certainly could have been in the running for Outstanding Production. Screwball comedies were not always excluded from the prestigious award competition. Frank Capra’s It Happened One Night won Outstanding Production in 1935. Regardless, Bringing Up Baby was not nominated for a single award in 1939. By this time, stars Katharine Hepburn and Cary Grant were well-respected actors in Hollywood, but their hilarious performances in Bringing Up Baby were not worthy of recognition according to the Academy. Hawks’ film is full of subtextual dialogue and brilliantly masked sexuality that was required in order to keep the sauciness audiences wanted but get past the Code restrictions of the time. The films actually nominated for Outstanding Production that year were not nearly as original and unheard of as Bringing Up Baby, but snubbing the film hasn’t kept modern audiences from returning to it eighty-three years later. The Outstanding Production award for 1939 went to You Can’t Take it With You. (Emily Kubincanek)

72. We Need to Talk About Kevin (2011)

How can you possibly tell the story of a troubled child and his mother without making it feel exploitative, overwrought, and cliche? Director Lynne Ramsay found a way in her film We Need To Talk About Kevin, which follows Eva (Tilda Swinton), a mother in the wake of her son committing a massacre at his high school. It’s deeply disturbing subject matter, but Ramsay stays away from excessive violence, focusing instead on Eva’s nonlinear self-reflection as she drifts through space and time, thinking about what she did to raise such a child. This is a film about motherhood — not perfect motherhood or monstrous motherhood, but the honesty of motherhood in an extremely rare and distressing circumstance. Ramsay allows Eva to regret her pregnancy, her motherhood, and her actions without making her a villain. Paired with Seamus McGarvey’s gorgeous and red-soaked cinematography, We Need To Talk About Kevin is a devastating and honest look into motherhood and grief that exists outside of the bounds of typical Hollywood cinema. (Mary Beth McAndrews)

71. First Cow (2019)

First Cow is a period movie that does that rare thing: instead of freezing history under an impenetrable layer of museum glass, it bridges bygone centuries to bring the past right into the sensual present. From the rain-gladdened greens of the Oregon forest to the redolent way Chris Blauvelt’s camera adores Cookie’s honey-glazed oily cakes, First Cow conspires to make history alive in a way that seems to summon up all five senses, despite only having access to two. And with Kelly Reichardt at the helm, this film is immediate in an emotional sense, too. It doesn’t just gently unearth tenderness out of a famously cutthroat context — a feat in itself — but also foregrounds Cookie and King-Lu’s friendship in a way that nudges us away from considering the past exclusively in terms of capital-H History. First Cow’s gratifying curiosity about the little details establishes a poignant fluidity between the then and the now, and, in its opening and closing shots, impresses on us the unfathomable scale and depth of history: innumerable lives, as fully-lived as our own, stretching across time. It’s impossible not to feel Reichardt’s filmmaking on a visceral level. That it didn’t occupy one of the year’s two vacant Best Picture spots — or a single nomination in any other category — says far more about the Academy than it does First Cow. (Farah Cheded)