“Teddy Perkins” is Still Daring and Terrifying

The most ambitious episode of ‘Atlanta’ to date is a harrowing thriller, a dark comedy, and a layered tragedy.

This essay is part of our series Episodes, a bi-weekly column in which senior contributor Valerie Ettenhofer digs into the singular chapters of television that make the medium great.

Each person who watches the Atlanta episode “Teddy Perkins” has a different what-the-fuck threshold, a point at which the sheer ambitious absurdity of the entry becomes crystallized in our minds as TV history in the making. For some, it’s when they realize that the titular shut-in’s Winnie the Pooh-like voice sounds unnervingly familiar. For others, it’s when Teddy shows Darius (Lakeith Stanfield) his museum room, complete with a faceless mannequin stand-in for his abusive, idolized father. For me, it was when I realized, as the episode aired for the first time in April 2018, that it was going to be an uninterrupted 35 minutes, a slab of rubber-band-tight tension presented without commercial breaks.

Even before we met Teddy Perkins, Atlanta was never going to be a run-of-the-mill show. When it began in 2016, series creator, writer, and star Donald Glover used a back-lot couch as a recurring set to lend Atlanta a sitcom-y bit of familiarity for nervous network execs, but this was a Trojan horse: he was never aiming to make the next Friends or Cheers. Early on, Glover compared the series to Twin Peaks, and later, to an obscure direct-to-video Looney Tunes movie. By the midpoint of season two, the surreal series about an Atlanta-based rapper and his crew had already featured an invisible car, a mythical German creature, a live alligator, Black Justin Bieber, and a drug-dealing, murderous re-imagining of the hip-hop group Migos.

Yet, from the start, this episode was different. “Teddy Perkins” is the first chapter of Atlanta to center solely on Stanfield’s Darius, the breakout character who’s like a stoner version of Kramer from Seinfeld (the only sitcom reference that does apply to the series) doling out conspiracy theories and obscure references to side stories that are both hilarious and bizarre. Viewers already knew from experience that Darius is always getting mixed up in off-the-wall scenarios — like trying to make money by trading a sword for a dog to breed puppies — yet nothing could prepare us for Teddy.

When the episode begins, Darius is driving a U-Haul out to a secluded area to pick up a piano with rainbow-colored keys that he found online. He stops at a store where he buys a trucker hat with a Confederate flag that says “Southern Made,” then changes it to “U mad” with a red Sharpie. When he pulls up to the luxe mansion that matches the address that’s been given, he’s listening to Stevie Wonder’s “Sweet Little Girl.” He doesn’t know it yet, but Darius is about to become a Black man in a horror movie, a loaded role within the history of the genre. And like the protagonist of Jordan Peele’s Get Out (which came out between the series’ first and second seasons), Darius is clever and on high alert, adaptable to change yet unperturbed, in a practiced way, by the danger of the situation.

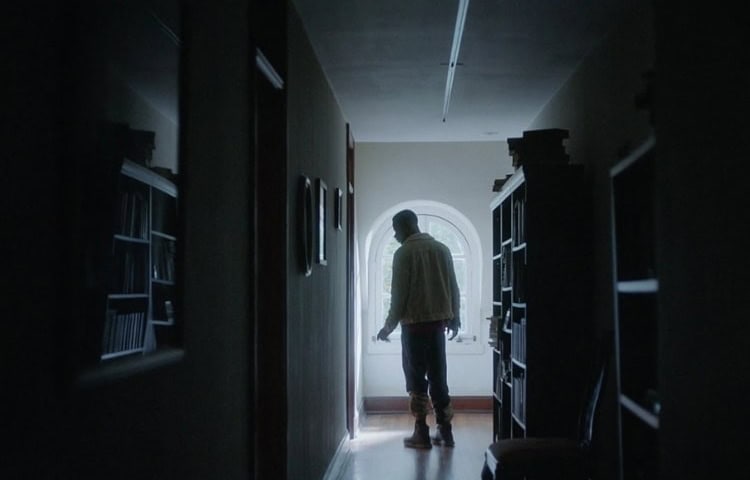

“Was that Stevie?” a reedy, strange voice asks him from the shadows as Darius steps into the house. This episode, directed with precision and grace by Hiro Murai (who would later bring us Glover’s “This Is America” video), is draped in shadows and surprising framing techniques. When Teddy Perkins steps out of the corner, we immediately know something is off. He’s a short man in a wine-colored robe with a face like a ventriloquist’s dummy — an obvious hairpiece, carved-out cheekbones, thin line eyebrows, and icy blue eyes. Atlanta has long-since been preoccupied with the idea of whiteface; in the episode “B.A.N.” a man claims he is transracial, while an episode earlier, in “Value,” Van (Zazie Beetz) has a student who has painted his face chalky pale. These moments are sharp inversions of the garish and offensive tradition of blackface, but Teddy isn’t immediately recognizable as an example of such. At first, we just know something is off.

Glover played Teddy Perkins. It’s common knowledge now, but on the night that “Teddy Perkins” aired, it was a rare surprise for live TV viewers, discovered merely through observation without any direct confirmation from the series’ star. “And Teddy Perkins as himself” reads the baffling title card at episode’s end, as if Murai and Glover knew we’d be searching the credits for something that would make sense of what we’d just seen. Months later, at the Emmys, Teddy Perkins was there and hugged Bill Hader when he won an award. Jarringly, a cut to the audience revealed that this version of Teddy Perkins wasn’t played by Glover, and his Emmys identity still remains unknown. The episode, by that point, had become lauded as the most unnerving thing viewers had seen on TV in ages: it is slow-burn horror turned into event television turned into a sustained and freaky prank on everyone who dares to watch.

“Teddy Perkins” isn’t all shock value, though. The half-hour that unfolds is a cross between Whatever Happened To Baby Jane? and the true Hollywood story of troubled celebrities like Michael Jackson, with points of dark humor and unexpected poignancy. First, Teddy eats an ostrich egg (“an owl’s casket”) in front of Darius. Then the two debate rap as an art form. Eventually, Teddy tells Darius the story of his brother, Benny Hope, who was a beloved musician before a rare disease made him unable to go in the sunlight. From there, things steadily and unpredictably tumble out of hand until, at episode’s end, Darius witnesses the murder-suicide of Teddy and Benny.

Much has been written about the two brothers at the center of “Teddy Perkins,” and for more on the significance of Teddy, Benny, and their father, I recommend reading great interpretations by writers of color like Leigh-Ann Jackson and Angelica Jade Bastién. There’s a reason this bottle episode immediately fascinated viewers and fans, drawing us further in to analyze it more than any other: every motion, shot, and interaction of the terse psychological thriller feels important and intentional — down to those awkward silences. When I spoke with episode sound editor Trevor Gates, he said:

“Perceived silence is not actually the absence of sound, it’s an isolation of sound. The viewers are hearing something but you have to craft what they’re hearing with extreme articulation for them to perceive it as quietness or silence. In the house with Teddy Perkins, it was the air. It was cold and it didn’t have any air condition or any technology. It encompassed the space that felt vast, so that was something that really helped us hold the silence.”

The vast labyrinth of Teddy’s house is appropriate for an episode that’s partly about getting lost in nostalgia to the detriment of progress. We — Darius and the viewers — follow Teddy through a sitting room and hallways, up the stairs, down into a basement, and into the museum-in-progress, the centerpiece of the episode. In this episode, Murai often uses stark shots of doorways, silhouettes, and photographs to eerie and meaningful effect, creating tension within a single frame in a manner that evokes Alfred Hitchcock and other horror auteurs. The final scene in the house is haunted by untapped sorrow that reverberates through the piano music in the background, even as Teddy speaks glowingly of his father’s abuse in the name of artistic perfection. “Not all great things come from pain,” Darius says a moment later, at gunpoint, his even-keeled composure finally cracking. “Sometimes it’s love.” Stanfield is fantastic here, delivering a powerful thesis plainly and truthfully, even though Teddy, who is convinced suffering is necessary to create great works, doesn’t listen.

“Teddy Perkins” manages to plumb the depths of the psyche to explore the line between greatness and tragedy, the unsustainable pressure put on Black artists, and the open wound of intergenerational trauma, all without offering easy answers. “Teddy Perkins” manages to frighten viewers half to death with unpredictable scenes that take sharp turns where you least expect them to, and with a setting designed for maximum tension. “Teddy Perkins” is somehow, in all of this, gut-bustingly funny — jokes about voice notes, bottled water, and one of the dads from The Breakfast Club are executed with bizarre perfection. And finally, with Murai at the helm, “Teddy Perkins” is a visual wonderland, teeming with rich shot compositions and film-geek-satisfying sequences.

In the end, there isn’t a simple last word. There’s just blood on the piano keys, and Stevie Wonder playing us out.