The Films of David Fincher, Ranked

With the release of ‘Mank,’ it is now time to rank.

5. The Game (1997)

A feral puzzle of absurd corporate antics, Fincher’s third film posits a horrifying question that no other filmmaker has dared to ask: What if Sean Penn was your brother? Apparently, he’d “gift” you a life-threatening, Truman Show-esque game experience that sends you on a shambolic chase and leaves your house and psyche in ruin.

At a time when forty-something Michael Douglas was the height of successful banker sex appeal, Fincher had an idea: throw him to the fucking wolves. From the second that Douglas walks into that office to the moment he sees Penn holding a tee that reads “I Was Drugged And Left For Dead In Mexico And All I Got Was This Stupid Shirt,” The Game is an absolutely gripping cerebral bender.

Shot by the late, great Harris Savides, whom he would bring back for Zodiac, The Game shines as one of the most gorgeously and energetically shot thrill rides in Fincher’s oeuvre. It also says a lot about Fincher that he was able to turn a screenplay from the notoriously subpar duo of John Brancato and Michael Ferris (see: Catwoman) into a near-masterpiece. Fincher has never written his own screenplay, but his fingerprints end up all over them.

Buried at the beginning of a career as strong as Fincher’s, The Game can be easy to overlook, but it set a precedent for his preternatural ability to evoke mystery – a mystery that far exceeded the more common procedural inquisition of Se7en, and one that would eventually run through the veins of Fight Club and Gone Girl, sending more spine chills our way. (Luke Hicks)

4. The Curious Case of Benjamin Button (2008)

It wouldn’t be fair to call The Curious Case of Benjamin Button Fincher’s most underrated film. It was commercially successful, received more Academy Award nominations in 2008 than any other movie, and walked away from the Oscars with three wins. The sprawling, romantic epic led by a wonderfully pensive performance by Brad Pitt was, suffice to say, a pretty big deal. And yet, reception seems to have cooled on the film. For most, it exists somewhere on a scale between sentimental Oscar bait and “it’s fine, but, like, who has three hours?” Even the people who like it don’t love it.

At least, this is what I’ve come to accept in my twelve-year long process of attempting to understand how anyone with a beating heart can view this beautifully melancholic chronicle of the 20th century told through the story of one peculiar man and not become enchanted by it. Sure, the film can be a touch schmaltzy, but there are images that capture something ineffably beautiful as only film can.

I think of Daisy (Cate Blanchett), Benjamin’s star-crossed lover, dancing in the moonlight, the lines of her body silhouetted against the twinkling reflection of water; I think of Daisy and Benjamin reflecting on their own images and the fleeting moments where they meet in the middle; I think of an elder Daisy kneeling to lay a kiss on the small boy next to her, a simple and gentle act made unspeakably sorrowful by two and a half hours that preceded it.

This is Fincher at his most sincere and his most heartbreaking, neither of which are traits I would have ever used to describe him before 2008. It’s a rarity, but an incredibly special one. (Anna Swanson)

3. Gone Girl (2014)

My go-to line when discussing Fincher with friends, family, and, frankly, anyone who will listen, is that Gone Girl isn’t his best, but it is my favorite. That’s not to say it isn’t impeccably well made with the dedication that I’ve come to expect from Fincher, or that it’s not one of the greatest films of the last decade. It’s just that this film both projects and feeds an obsession like few films do, it taps into something that makes it endlessly rewatchable, and it’s an incredible testament to craft and collaboration that I can’t get enough of. No matter how many times I watch the film, its twists never fail to floor me, and its bountiful treasure trove of precise details means there’s something new to be found on each viewing. It’s also wickedly hilarious, with a sense of humor deftly on the pulse of cynicism and absurdity.

Anyway, we’ll be here all day if I continue to discuss all the brilliant qualities of this modern genre landmark. The point is that it’s impossible to imagine any other director making this film work as well as it does. Between the dueling unreliable narrators, the mid-way plot shift, and the sheer audacity of where Gone Girl dares to go, it’s a miracle that Fincher and writer Gillian Flynn pulled it off. Successfully making this film required the vision to see the big picture and the dedication to minute details to ensure it would all come together. I still find myself amazed that it even exists. I’m so glad it does. (Anna Swanson)

2. The Social Network (2010)

I remember the first time I watched The Social Network like I remember learning I could eat olives (read: favorite food) straight from the jar instead of waiting for a few of them to end up on a salad. Beaming, I popped ten of those suckers on my fingers, went to town, rinsed, and repeated until I passed out at the dinner table from sodium intake. It was incredible.

The Social Network is an invigorating reminder that no single minute of a film has to be inert. From the Phoenix initiation sequence to the stunningly orchestrated rowing race to the “fuck-you flip-flops,” any and every scene could be a favorite. It posits that perhaps the tastiest cinematic treat is one that renders its audience gleefully captivated until they transcend into a fugue dream state.

The Social Network is an inimitable marvel, a seminal film that marries Fincher’s greatest talents and sensibilities into one sweeping historical narrative only five years removed from its happening – in other words, a work of total control. Fincher isn’t the type to write, produce, edit, and/or shoot his films on top of directing, but the fact that he isn’t co-credited for any of those things is a bit of a misnomer.

He works tirelessly alongside his collaborators to bring out the best in them and wisely knows when to step back once he’s provided proper inspiration. For example, five- and six-time editors Kirk Baxter and Angus Wall delivered a razor-sharp cut that plays in tandem with Aaron Sorkin’s endlessly scintillating dialogue to keep us on our toes at all times, even when we’re sitting through a deposition. The three of them won Oscars for their contributions.

Fincher also employed Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross for their first ever film score, which led them to little gold men, as well, and thrust them into movie-composing careers afterward. Jesse Eisenberg’s performance as the slimy, whipcrack Facebook founder remains his sole Oscar-nominated performance.

The only let-down of The Social Network is realizing how singular it is after looking for something to scratch the same itch and coming up miles short. Few can galvanize viewers as deliberately as Fincher. They’ll put some olives on the salad, but they won’t hand you the jar. And so, I say to them, “You have part of my attention – you have the minimum amount. The rest of my attention is back at the offices of [David Fincher], where [he is] doing things that [almost] no one in [film is] intellectually or creatively capable of doing.” (Luke Hicks)

1. Zodiac (2007)

I need to be honest, I don’t know how to write about Zodiac. How do you take a film like this — Fincher’s magnum opus, a true-crime epic, my pick for best of the 21st century — and neatly put its achievements into a few hundred words? This film, about three men united by the unshakeable investigation of the eponymous serial killer, surely deserves more than that.

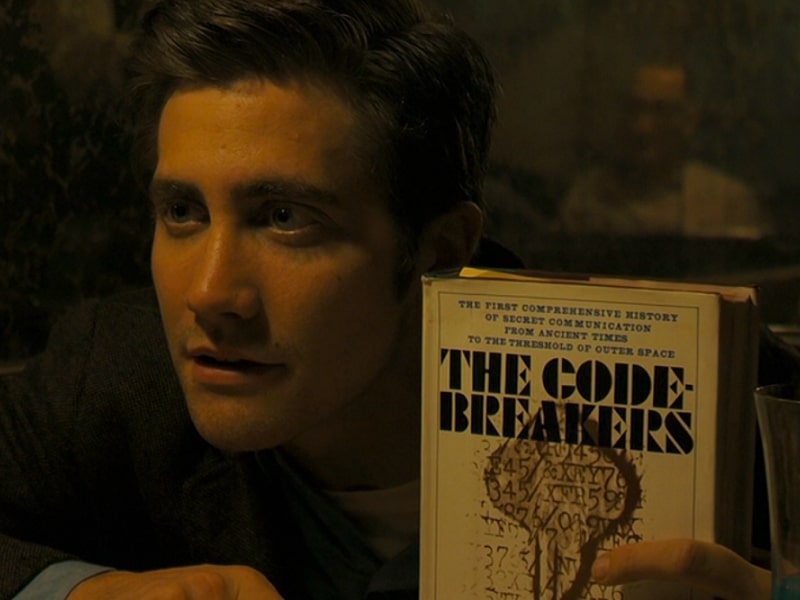

In lieu of attempting to successfully surmise the incomparable effects that this film creates, I’ll highlight one scene. Or rather, one line. Late in the film, obsessive armchair detective Robert Graysmith (Jake Gyllenhaal) sits opposite actual detective Dave Toschi (Mark Ruffalo) discussing his theory of the case. He outlines the facts and presents his suspect, explaining that at one point he lived in close proximity to the workplace of a victim. Less than fifty yards, to be precise. And how does Graysmith know that? “I’ve walked it.”

He’s walked it. Of course, he has. We’ve seen him gripped by the grueling need to know, a compulsion that is at once unwavering and unbearable. It’s a credit to the collaborative process that after observing the two hours preceding it, we understand how much this line serves as a thesis. Gyllenhaal and Ruffalo deliver subdued career-best performances. David Shire’s score rings like a note you can’t get out of your head. Harris Savides’ cinematography is unvarnished enough to not portray murder as tantalizing while having a naturalistic clarity surely enabled by the film’s landmark use of digital cameras.

Still, it must be said that all of this is moot without Fincher at the helm. He’s a director who understands dedication like the back of his hand. With a puzzle laid out before him, Fincher is consistently committed to solving it, with no process being too extreme or exacting that it’s not worth it in the end. David Fincher, I imagine, is someone who would walk it. (Anna Swanson)

This article was co-written with Anna Swanson.