The Allure and Shock of ‘Black Narcissus’

Powell and Pressburger created iconic films in the 1940s. ‘Black Narcissus’ is one of their greatest masterpieces.

The influence of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger reaches far into the annals of film history. The duo was famous for many works ranging from The Red Shoes, The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, A Matter of Life and Death, and Black Narcissus.

Black Narcissus, in particular, was so unlike anything directors were making in 1940s Britain. The film fuses sexuality and religion into a petri dish of unrelenting turmoil. It is also the product of masters on all sides of production bringing to fruition a truly memorable film.

Black Narcissus was an intriguing glance into the politicals surrounding Britain during 1947, especially in how they viewed India and Pakistan who were fighting for independence. There is definitely a conflict between two religious principals and how they can possibly exist. The nuns featured in the movie seek to bring about change to a culture and people that have been unchanged for centuries. It almost foreshadowed what was to come because no matter how much Britain tried to have India and Pakistan under their control, they were going to live by their religious ideals and ways of life.

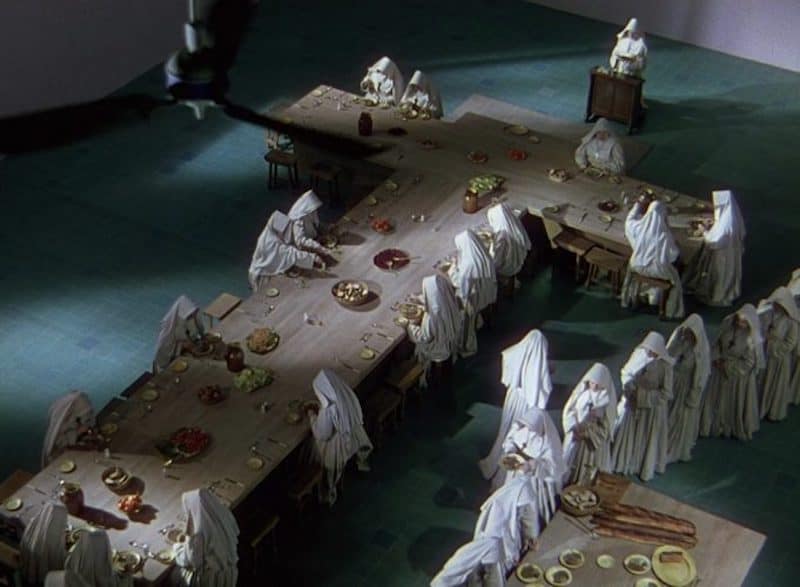

Perhaps even more famously, there is also flourishing female sexual desire and how repression can lead to dangerous results. The story follows a group of nuns who have been given the task of opening a convent high in the Himalayan mountains by invitation of an Indian ruler. Sister Clodagh (Deborah Kerr), is the sister superior in charge of getting everything settled. They will be essentially renovating an old “castle” (which is actually a house where the general used to keep his many women) to teach the locals and provide care for them. The locals are often depicted as simple-minded and promiscuous, adding to the air of unease surrounding this strange location. The nuns, who are seen as chaste otherworldly beings to the people of the village, are influenced by the people and atmosphere. This leads to old memories haunting the nuns once again, as they dream about the life before they had taken the cloth.

When the film was released in 1947, Black Narcissus had its fans as well as its distractors. Thomas M. Pryor of the New York Times called the picture “an artistic accomplishment of no small proportions.” While others were quick to appoint the film “Brief Encounter in the Himalayas.” Time magazine gave it a scathing review saying, “Black Narcissus remains a striking sample of bad art, combining the least attractive features of slick and long-haired fiction.”

One group, in particular, condemned the film in the US. The Catholic Legion of Decency went on the attack against the film as early as April 1947. When their review was published in the Catholic weekly The Tidings, the judgment was harsh: “It is a long time since the American public has been handed such a perverted specimen of bad taste, vicious inaccuracies, and ludicrous improbabilities.” Black Narcissus needed to be edited for an American audience, removing sequences of flashbacks from Sister Clodagh and some instances of suggestive dialog. There was little chance of this film featuring nuns appearing unedited, especially considering the underlining female sexuality.

The three women most inherently troubled by their past and desires throughout Black Narcissus are Sister Clodagh, Sister Ruth (Kathleen Byron), and Kanchi (Jean Simmons). Kanchi is a local girl, who has little wits about her, but she is beautiful and she uses her sexuality to her advantage. Perhaps she believes the only opportunity in her life consists of being married to a prominent man. One could say that she is successful in her endeavor since she gains favor with the young general. Feminine charm might be the only thing Kanchi is aware of, but Sister Ruth is deemed ill for her regressions to feminity. As a woman of the cloth, she is to deny herself of such longings. That is good in theory, but Sister Ruth is not able to follow through in practice. She takes even the slightest pleasantries from Mr. Dean (David Farrar), a local Englishman tasked with helping the nuns with whatever they need, as a sign of endearment. Sister Ruth longs for Mr. Dean, so much so, that she mentally believes that Sister Clodagh is her competition for his favor. Sister Clodagh does long for something from high in those mountains, but it is not Mr. Dean. She dreams of a former romance where she always believed that she would be happily married, but that her suitor had other ambitions in mind. She turned to the cloth because of that romance but hasn’t thought of it until her time in the Himalayas.

Certainly, there is a lot to admire about Black Narcissus. From the matte paintings of the landscapes, the impeccable cinematography from Jack Cardiff, and arguably a career-best performance from Deborah Kerr there is a lot to praise. While the film has never disappeared from consciousness, Martin Scorsese’s love of the film has certainly helped it endure and continue to be part of the conversation in film history. When the film was recently restored in 2010, many reviewers were reintroduced to the film. Slant Magazine’s Joseph Jon Lanthier said of the film, “the baroque Pinewood sets, the orchestra of lights, and the dexterous cast all lie prostrate before their director’s penetrating and life-bestowing lens.” In this particular case, he is referring to Black Narcissus‘ eroticism as being second to the craftsmanship on display. For everything that Black Narcissus challenged in the 1940s (female sexuality and religion among those), it remains a timely classic 70 years later because of the craft on display from all the principal contributors. Powell and Pressburger defined an era in British filmmaking and with Jack Cardiff behind the camera they created iconic cinematic treats that certainly includes Black Narcissus.