‘Memento’ and the Unreliable Image

In his second feature film, Christopher Nolan considers the lengths a director might go to manipulate their viewer.

Christopher Nolan is hailed as one of modern cinema’s most successful puzzle-makers. In the perplexing Inception (2010), he broke cinematic grounds by considering the murky relationship between dreams and reality. Similarly, in his recent blockbuster, Tenet (2020), Nolan rejects ideas of linear time entirely in a manner that most viewers aren’t able to fully grasp on a first watch.

Nolan’s second feature, Memento (2000), clearly set the precedent for the director’s complicated storytelling sensibilities. Told backward, the movie eagerly disrupts linear time. Because of its bold and novel framework, it is often considered to be concerned with the out-of-order timeline gimmick before it is concerned with anything else. But where Memento’s complications really lie is in its understanding of the image, and how that image is affected by solipsism.

Memento opens on Leonard (Guy Pearce) killing a man who is later revealed to be a cop named Teddy (Joe Pantoliano). Sequentially speaking, this is the last thing that happens in the story. But the events leading up to this pivotal moment are revealed backward, so viewers only gain insight into the murder’s true inception right before the credits begin to roll.

Throughout the movie, the audience learns more and more about Leonard’s character. He lived a relatively normal life until, one night, two unidentified men broke into his house, raped and seemingly killed his wife (Jorja Fox), attacked him, and subsequently gave him brain damage that left him unable to form new memories. So, the last thing Leonard remembers is his wife being murdered. Everything after that, he forgets after ten minutes.

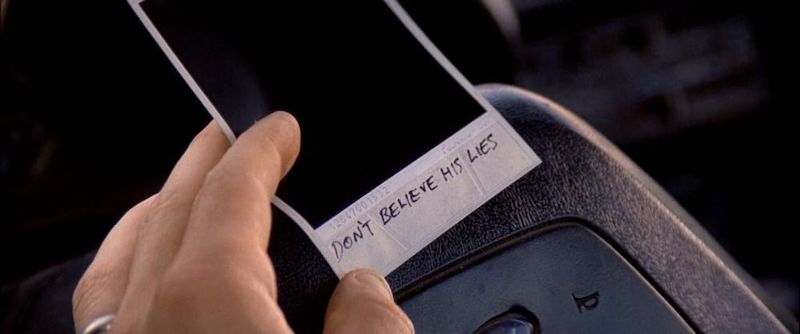

In order to remedy his nonexistent memory and hunt down his wife’s killer, Leonard uses mementos — namely, photographs and tattoos — to remind himself of his objective. Because of this, he not only meticulously weaves a narrative for himself but also for the film audience, too. When watching a movie, an audience tends to presume that what is being presented to them is truthful. Or, at the very least, is not deceitful. But when it comes to Memento, these are not realistic expectations.

Leonard ultimately bases the majority of his life after his accident on a meager series of images. This, in turn, makes him less reliable as a narrator and causes his narrative to be one that is highly subjective. He is driven by a very limited supply of information that he has no real reason to doubt. But, while this is a valid analysis of Memento’s protagonist, viewers often fail to consider that they are ultimately just as unreliable as Leonard.

Indeed, when watching a movie, the first image often informs the remainder of that movie. This only makes sense, as the audience has nothing else to go off of, so they trust it unquestioningly. In Memento, it’s the image of Leonard murdering Teddy. And so, as it is revealed that Leonard’s wife has been murdered and that he is hell-bent on revenge, the audience does not question that Teddy is her killer. Instead, they just wonder what truths led him to that conclusion.

And this is one of the reasons that Memento is such a compelling allegory for filmmaking itself. The cinematic medium often presents materials with an air of assumed objectivity; the camera is set up in the middle of the action, and that action unfolds in front of it. But this is necessarily just an illusion. Indeed, these images are curated carefully for the audience, just as Leonard, unbeknownst to himself, curates his own twisted treasure hunt.

When looking closely, Memento doesn’t shy away from investigating the trickery of filmmaking. Sporadically, there are scenes of Leonard narrating his experience in a motel room, which play forward. These scenes are stylistically divergent from the rest of the movie, as they are in black and white. Already, this is a jarring effect that takes the viewer out of their perceived “reality,” especially in contrast with the multitude of scenes that have already been in color.

In addition, these scenes fall under the pretense that they are part of this separate film noir, with a dramatic, almost parodic voiceover, cool, dark aesthetics, and a mysterious crime plot. Not only do these scenes feel out of place visually, but also thematically. They remind the viewer that their experience is being tailored to manipulate them, just as Leonard ultimately manipulates himself.

At the end of Memento, it becomes clear that Leonard is indeed the director and manipulator of his own life. Teddy reveals to him that he was a cop on his wife’s case and led Leonard to the guy who killed her (though she did not actually die), and allowed him to exact his revenge. Despite having done this, however, Leonard’s memory issues did not allow him to receive the needed emotional catharsis he needed — at least not for more than ten minutes. Thus, he was doomed to remain on this infinite hampster wheel of retribution.

So, Teddy used this to his own advantage and sent Leonard on cat-and-mouse chases to hunt down criminals on the pretense that they are his wife’s killer, and do Teddy’s dirty work for him. When Leonard learns about this arrangement, he is enraged and decides to frame Teddy as his next victim, which will not only fulfill his anger toward him but also satisfy his need to feel as though he is perpetually on the hunt for his wife’s killer.

Leonard’s need to repeatedly unconsciously craft his own narrative mirrors a filmmaker’s way of subtly hiding clues under their seemingly straightforward film. Leonard leaves clues for himself in the form of polaroids and tattoos in order to trick himself, just as Nolan intentionally misleads his viewer by not allowing them to think there is any other option than that the protagonist is one on a quest for justice – and if he follows all of the given clues, the moral scale will finally be balanced.

The viewer begins Memento in Leonard’s head, and so they trust him. Just as he trusts himself. But the irony is that he is his own worst enemy. So he falls victim to himself, just as the audience falls victim to the director who ensnares them in a web of a narrative, of which he only allows them to see a small portion.